It is rare for a technology or service to evoke extreme opinions as LEO satellite constellations do. On the one hand, some would say that no constellation has managed to avoid bankruptcy. On the other hand, some believe that LEO satellites will eliminate the global digital divide. What I aim to highlight here is that the business case for LEO satellite constellations is not doomed to failure. However, it is a delicate business case that should not be burdened by unrealistic expectations. It is possible for LEO satellites to succeed; but doing so would require careful design, planning and patience.

The five critical elements to LEO success

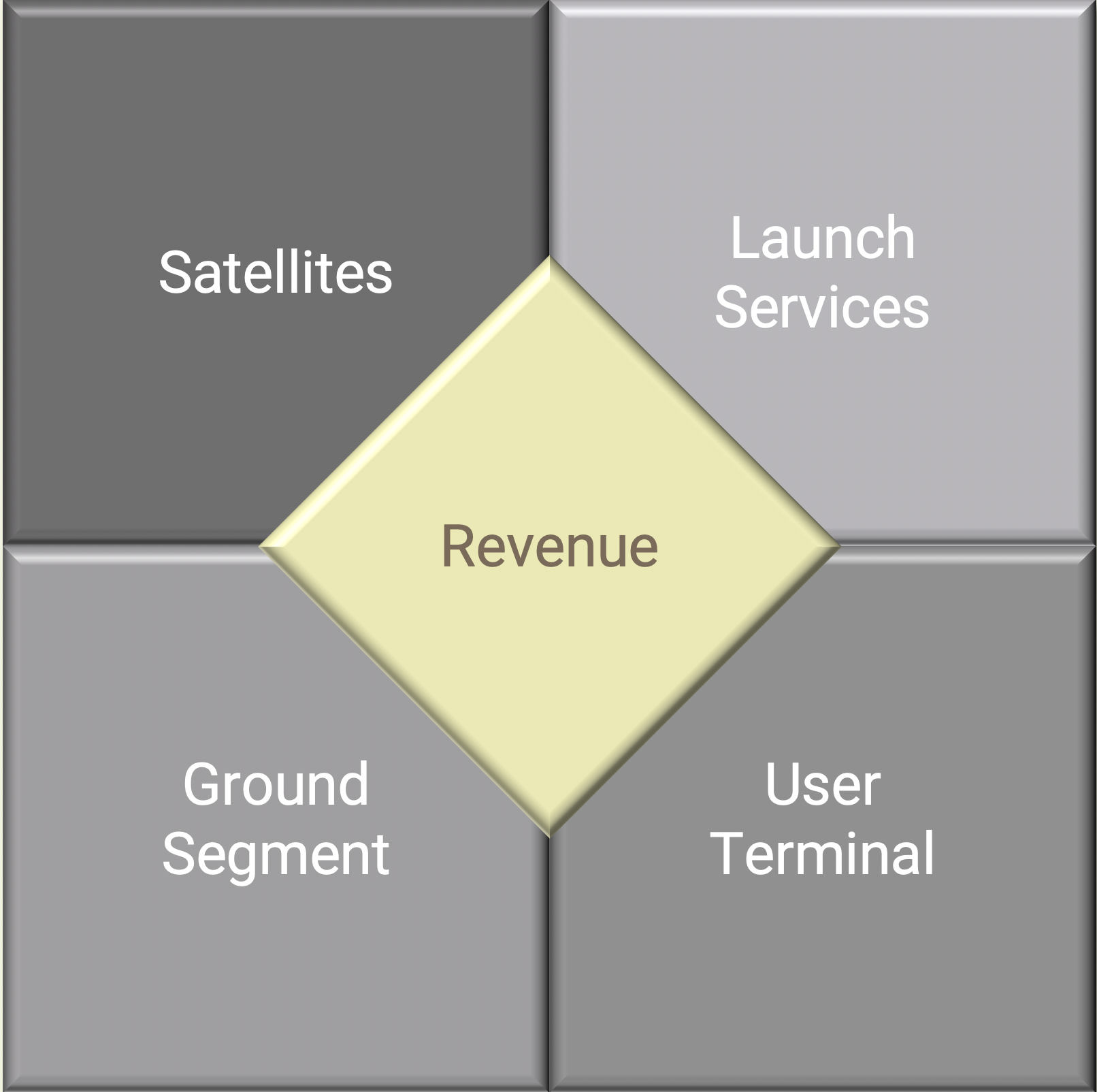

There are five key elements to the LEO business case. Four of these elements are on the cost side: the costs of satellites, launch, ground stations and user terminals. The fifth element is the number of subscribers that will drive revenue. These elements are interrelated with additional factors that govern their interdependency such as spectrum assets, performance metrics and quality of service.

The predictable costs

Satellite and launch costs, which are rather predictable, make for a sizable part of the total capex amounting to over 50% over the lifetime of the constellation. Large constellations with thousands of satellites, such as SpaceX and Kuiper, target a streamlined production process and bring the cost per satellite to below $1 m with around 100 units per month in production. Given a satellite lifecycle between 5-7 years and a business lifecycle of 20+ years, the number of manufactured satellites is at least 3-4x the size of the constellation. This underpins the potential economies of scale in satellite production and highlights the merits of long operational life for satellites.

The cost of launch has decreased to under $2,000/kg. The cost of launch for a LEO communication satellite weighing a couple of hundred kilos, amounts to around 50% of the cost of the satellite. However, constellations such as SpaceX and Kuiper have their own launch vehicles which could subsidize a part of the launch costs. In effect, these operators have reasonably good control to minimize the predictable capex.

The less predictable costs

The costs of ground stations and the user terminals are the wild cards. The first – cost of ground stations – is dependent on the service markets. This is where it becomes tricky as geographic expansion has to be considered carefully. Initiating a service in a new country could require new, in-country ground stations, irrespective of the potential subscriber base. Reducing the number of ground stations by introducing inter-satellite links (ISL) adds weight and power requirements, and increases cost. This leads to a delicate trade-off that is best optimized in the context of the use case, such as consumer access, enterprise backhaul, and/or mobile services.

The second – the cost of the user terminals – is primarily driven by volume. Constellations targeting consumer applications would typically use a form of electronically steerable antennas. This makes service adoption critical since the price of ASICs that enable beam steering depends on volume. This is also where we see rather optimistic and unrealistic forecasts reaching into the few hundred of dollars, tracking a cost curve similar to that of smartphones. However, given that a user terminal transmits a few watts of power, and given the potential number of subscribers supported by the network to meet service requirements, it would not be possible to achieve such a low terminal cost. In fact, a cost curve tracking wireless small cells is the more appropriate model. This would place the cost of a user terminal in the $1,000 range, for most practical numbers of supported subscribers.

The revenue levers

While a LEO constellation covers the globe, only a fraction of satellites would be actively servicing subscribers at any instance. Estimates for the utilization factor range between 4% to 25%. Utilization plays a pivotal role in determining the success of a constellation. It also represents a key weakness in the LEO concept: meeting the capacity requirement of a certain location on earth requires proportionally larger constellation to fulfill the demand. Consequently, LEO constellations perform best when the user-base is widely spread across the globe. The international aspect of LEO constellations is absolutely critical to their success.

Winning is possible

In our analysis, a LEO satellite with about 2 GHz of downlink user spectrum could support between 3,000 – 20,000 subscribers depending on the desired performance (e.g. 100 Mbps; 100 GB/month). A 4,000-satellite constellation designed for 100 Mbps service could support between 3 million to 20 million subscribers. Could these numbers lead to a successful business case?

The answer is a qualified yes, provided certain conditions are met pertaining to the parameters mentioned above. Our Monte Carlo simulations of LEO constellation techno-economic models, show a long time to breakeven typically around 7 years. They also show that the odds of downside in profitability are high with a cap on upside potential. Overall, the long-term scope of the business model raises uncertainties related to future earnings and costs.

Winning needs patience

The mechanics of the business case for LEO constellations require investors to be very patient. It is not sufficient to have deep pockets, but the ability to stick with the plan over the long term is critical. This requires a unique set of investors with long-term view and commitment. It could also help explain why no LEO constellation escaped from bankruptcy. Finally, as SPACs became a major vehicle for fundraising, one needs to question how these vehicles are aligned with the requirements of the LEO business case.

The post The business case for LEO satellite constellations: Walking a tightrope to success (Analyst Angle) appeared first on RCR Wireless News.